In a recent blog, I reflected on the idea that sometimes we miss a step when trying to motivate our students. We think about what we can do as teachers to set the conditions for motivated learning but maybe we need to think more carefully about students’ emotional starting points.

Being aware of student feelings and emotions can help us to plan and deliver better lessons, particularly when managing success and failure. As Mccrea (2020) says in Motivated Teaching “Expectancy is heavily shaped by prior success rate. The more successful we have been in the past, the more likely we are to invest in similar opportunities in the future”.

Students are more motivated when they feel competent to do what is expected of them. Boekaerts (2010) said that students who feel likely to succeed tend to “choose more challenging problems, invest more effort, persist for longer”. I recognise this in my own six-year-old son, who believes he is good at everything. At that age, it doesn’t occur to him that he has strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others; he believes he is clever, and that message is reinforced at home and at school.

Wigfield and Eccles (2002) found that children’s sense of competence generally declines as they get older. Older children compare themselves to peers and become accustomed to grading and evaluation procedures. While successful learners tend to use this information to work harder, students who are less successful find themselves lacking motivation without really understanding why. They switch off and, often, no one really notices when this happens.

So at some point my son will realise that he isn’t good at everything but I hope that the realisation doesn’t come as too much of a blow to him. I hope that between school and home, we can work together on the messaging that it is good to have talents in particular areas and to work hard at the things we struggle with. Most importantly, I hope we stop to notice how this realisation makes him feel.

Getting the Right Messages Across

The messaging we receive and the stories we tell ourselves are vital. When I was a student at school, I was surrounded by messaging that said I was clever; I was good at English and would do well. The messaging I received from the maths department, however, was that I couldn’t do it and I had no hope of passing my exams. The messaging from the maths set I was in told me that behaviour would dominate lessons and there would be very little maths covered. The messaging from my teacher came from the roll of his eyes every time I asked him to explain something to me for the second or third or fourth time. So, when I failed Maths GCSE, it was no surprise to anyone.

So how can we ensure that our messaging is on point? For me, this is about teachers knowing that everything they do, everything they say, communicates something to the students they teach. The way we speak to students, the way we frame activities, they way we present difficulty, all this matters.

As Boekaerts (2010) puts it:

“Teachers need to be aware that the motivational messages are embedded in their own discourse, their selection of learning tasks, and in their teaching practices. Students pick up on these unintended messages and appraise the climate as either favourable or unfavourable for learning.”

Maybe by being more mindful of the approaches we take as teachers, we can help our students to perceive the climate as favourable and beneficial.

Some of the ways I have done this recently are by:

- Dwelling on success

- Attributing Success

- Breaking it down

- Slowing it down

Dwelling on Success

We need to ensure our students experience the sweet taste of success. We shouldn’t give empty praise or ply students with messages that their achievements will be limitless, but we have it in our power to signpost successful behaviours and to celebrate good work. I think we need to be explicit as we go along about when students have been successful and let them bask in it. We need to dwell on that success with them, encouraging them to savour that feeling so that they can develop an appetite for success over time.

We shouldn’t just think about success as something we experience individually; we can also think about the collective endeavour of striving for success as a group. This might involve using some reflective questions at the end of the lesson or as part of an exit ticket that asks: what did we get right today? How did you contribute to the success of the lesson? What did you do well? What did others do well? What were the strengths of today’s lesson? Asking about how we have been successful together is an important nuance.

Attributing Success

As well as helping our students to feel good about their achievements, we also need to help students build positive associations over time so they can recall and make links to prior successes. We need to help students attribute success and failure correctly. If students feel that doing well was a fluke (they were just lucky this time) they are unlikely to be motivated by that achievement. They must own their successes and know why they did well otherwise they might not be able to use that experience as a milestone for future goals and aspirations.

Mccrea (2020) says that “only when pupils believe they were successful themselves and they attribute the cause to themselves – their own effort, ability and approach – will their expectancy increase” and that teachers can influence expectancy by “repeatedly messaging, through both our talk and action”.

One way we might go about doing this is by reminding students about the excellent work they did today, last week, last month, etc. The way we use our language can help make this explicit for students: “Remember that excellent point that Jacob made last lesson…”; “lets return to that model paragraph that Alice produced last week…”; “let’s revisit why Adiel’s answer was so good last month…”. This makes the success they experienced memorable and motivates them to work hard for it again.

Another way we can do this is by using the visualiser to look at a piece of student’s work, asking, ‘what makes this so good?’. By linking what is good in the model answer to successes students have had, they are likely to feel that improvement is possible. We might say something like “This is a brilliant example of using explanations and this is also something I saw in Emily, Mohammed and James’ essays”.

As Mccrea says, we need to influence expectancy through our talk and action. We need to make those successes feel current and relevant. Talking out loud and naming these achievements help students attribute success to their own effort.

Breaking it Down

As teachers, we need to make connections between what students feel they can’t do and what they do well already. In his book ‘Habits of Success’, Harry Fletcher Wood (2021) talks about the importance of breaking big tasks into bitesize chunks. He recommends we either break tasks down in advance of setting a task, or when students are doing the task and hit a bit of a wall. By breaking tasks down into the steps which will hopefully become automatic later, we put a spotlight on the process and point out the parts that students have mastered already.

When planning a scheme of learning on discursive writing recently, I predicted that at least one child wouldn’t know where to start. English teachers will know that this is a common problem with writing tasks! Realising that emotional starting points could be a bit of a barrier, I broke my teaching down into the following steps:

- Frontloading the thinking and planning.

- Taking a viewpoint and not sitting on the fence.

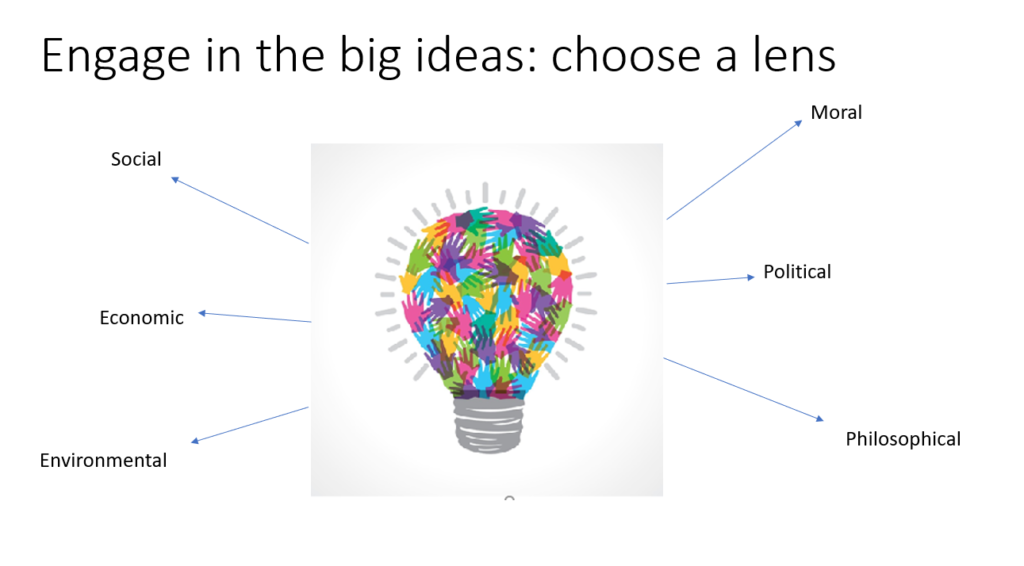

- Developing an argument through several different lenses.

- Planning the structure and sequence of the argument to include a main argument, a few supporting mini-arguments and a counter argument.

- Using a range of linguistic devices to engage their audience, enabling them to write with conviction.

We spent quite some time on points 1 and 2 above which focus primarily on thinking. I provided a lot of scaffolding about how students might go about planning ideas before even starting to consider writing. With point 3, I began to take the scaffolds away, asking students to identify the ‘big ideas’ they could draw on more independently.

I planned this sequence knowing that students needed to experience success early, something I also talked about in my Educating Northants talk back in March. By investing time in the pre-writing stages, students were able to experience success before beginning to compose a piece themselves.

Slowing it Down

In Mary Kennedy’s paper ‘Parsing the Practice of Teaching (2015) she makes the excellent point that “education is mandatory, but learning is not”. For students to engage with learning, they need to concentrate hard on challenging material. She tells us:

“School learning requires what Kahneman (2011) calls “slow thinking” the kind of thinking that requires concentration and effort. In contrast, most of life outside the classroom calls for “fast thinking” thinking that is reflexive and that allows us to jump to conclusions, rely on rules of thumb or re-use a habit we used in the past”.

I think it is our duty as teachers to recognise this tension and to present challenging material with an acknowledgement that students will struggle with it. Simply reciting knowledge or walking through a maths problem on the board is not going to cut it. Understanding that students need to think about something in order to understand it (Willingham, 2009), Kennedy recommends that teachers ask students to make a prediction or explain why something happened to help them see the causal relationships:

“These questions and prods are intended to help students to think about the underlying relationships and concepts that the teacher is addressing and increase the chances that students will see and understand those relationships.”

When I teach William Blake’s poem ‘London’, which students find incredibly difficult, I usually spend several lessons introducing and exploring some key concepts first, including ideology, hegemony and consent. These are difficult concepts to grasp so I take my time, give them space to explore the meanings of the words and help them make connections to knowledge they have encountered elsewhere in the curriculum.

This means that when we come across the phrase “mind-forg’d manacles” in stanza 2, students are already comfortable with the notion of the hypocrisy Blake was challenging in the social institutions of his time. In the past, when I tried to explain the meaning of this line as I read the poem aloud, I found it difficult. It is not the sort of thing you can explain in a nutshell or write in a glossary; it takes much more unpicking than that. Slowing down and giving time to do the unpicking has made all the difference when studying poems with difficult concepts like this.

The four approaches discussed here are by no means an exhaustive list, but I hope they help to illustrate the importance of using students’ emotional starting points. Perhaps this is the kind of data that we should be looking at more in schools.

References

Boekaerts, M (2010) The Crucial Role of Motivation and Emotion in Classroom Learning. Available to access at: The crucial role of motivation and emotion in classroom learning | The Nature of Learning : Using Research to Inspire Practice | OECD iLibrary (oecd-ilibrary.org)

Fletcher-Wood, H (2021) Habits of Success. Routledge.

Kennedy, M (2015) Parsing the Practice of Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education. Available to access at: (PDF) Parsing the Practice of Teaching (researchgate.net)

Mccrea, P (2020) Motivated Teaching. Peps Mccrea.

Wigfield and Eccles (2002) Motivational Beliefs, Values and Goals. Annual Review of Psychology Vol.53. Available to access at: eccles-wigfield-2002-motivational-beliefs-values-and-goals.pdf (wordpress.com)

Willingham, D (2009) Why Don’t Students Like School? Jossey-Bass.